You know Charles Schwab as our founder and the man who helped make investing accessible to everyone. But did you know he was a door-to-door insulation salesman? Or that he almost flunked out of college? Or that he raised chickens as a boy? Now you can find out where it all started for Schwab (the man and the company), and how he went from dyslexic student to Wall Street disruptor, as the company went from start-up to industry leader, in the new documentary “Chuck” by Oscar-winning director Ben Proudfoot.

Charles Schwab (00:00:57):

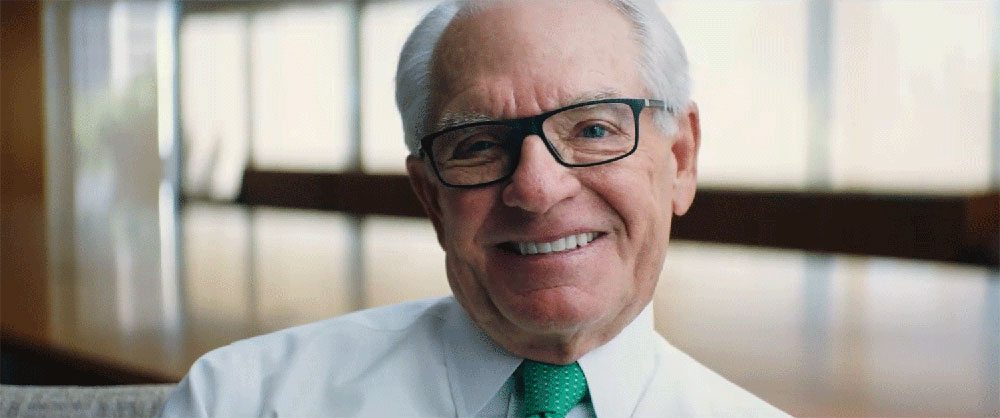

What is my name? My given name is Charles Robert Schwab, the Founder of Charles Schwab and Company.

(00:01:25):

These are tinted, but I'll put them on. There I am. My prescriptions changed a little bit, but this is basically what I looked like. However, my hair was a little bit of a different color, back in '75.

Latasha Poindexter (00:02:30):

My name is Latasha Poindexter and I've been a security officer at Schwab since 1992. And I was born in Memphis, Tennessee. My dad was a laborer. My mom stayed at home, four kids. We were pretty happy kids coming up. We just didn't have that much. Just said, I wanted to be a millionaire by the time I'm 30. Making, building, creating, contributing. That's right. I graduated in '82, '82.

Speaker 3 (00:03:22):

Good evening. Unemployment went up last month. This means that 9,600,000 people are now out of work looking for jobs.

Speaker 4 (00:03:29):

Some experts are becoming fearful that rising interest rates will cut short any economic recovery. They say things could get so bad that the current recession will look like a picnic.

Ronald Reagan (00:03:38):

I believe in these months ahead, the recession bottomed out and we're going to see interest rates begin to fall.

Speaker 6 (00:03:44):

Economists still believe the unemployment rate will climb above 9%.

Latasha Poindexter (00:03:48):

It was not a great time in the economy. I did get very, very close to one job. It came down to two candidates. It was a pharmaceutical sales job. We sat down with the regional sales VP at his house. We were the last two candidates to interview and they were going to pick one of us. He gave us a scenario; would I promote this drug for something other than what it was approved for? Ethically speaking, I couldn't and the other candidate said they could. And so when I found out basically that I didn't get the sales job with the pharmaceutical company, my professor told me why I didn't get it, because I thought I did great in the interview. He said, "Because you were too honest." So, too honest.

(00:04:55):

And so from the temp agency, I found different forms of employment. I worked for Bank of America, verifying signatures, at night. They were at front of Pacific, so I had to walk up Montgomery to my job and I would always look to my left. I had always walked by the building. Said, "Oh, okay. Charles Schwab." Never knew anything about investing and trading. So I would hi and bye with these traders for months and they would tell me what they were doing.

(00:05:38):

I got to talk to some of the staff that was working for Schwab at the time and then they would tell me that they would get stock every quarter. I said, "What kind of company does that just for the little guy?" The whole concept of helping the little guy achieve wealth, leveling of the playing field and they said, "We like her," and so they told the management. And so February of 1992 was when I finally got a chance to work for Schwab. Me, I would like to leave more than my dad left. Yeah.

Speaker 7 (00:06:25):

Merry Christmas.

Speaker 8 (00:06:25):

Merry Christmas.

Latasha Poindexter (00:06:29):

Provide for those little ones for the future. My nieces and nephews, that's why I'm here, so I can leave a little something more. My dad, he had a little small retirement with the trucking company he worked for. Now, his father left him a shoebox. And of course you want to know what's inside the shoebox, right? I'll tell you by the end of this interview.

Charles Schwab (00:07:23):

I was born in 1937, end of a depression period in America. Life was about limited resources. Every family had ration books and had coupons to get certain kinds of commodities, whether meat or eggs, but we were in a rural community and my father did some legal services in exchange for a lamb, or something like that.

Speaker 9 (00:07:51):

Why does he bring you all this stuff?

Speaker 10 (00:07:55):

He's paying me for some legal work I did for him. Cunningham's are country folks, farmers. The crash hit them the hardest.

Charles Schwab (00:08:04):

That's what you did back then.

Speaker 11 (00:08:07):

Like your president, I speak of a long and a hard war. The broad flow of munitions in Great Britain has already begun.

Charles Schwab (00:08:18):

I remember we had this war against a lot of people.

Speaker 11 (00:08:21):

Japan, Germany, and Italy have all declared and are making war upon you.

Charles Schwab (00:08:27):

Well, I used to see it every Saturday when I went down to see the cartoons and so forth. We'd always had a news reel, much of which was devoted to the war.

Speaker 11 (00:08:37):

And a quarrel has opened, which can only end in their overthrow, or yours.

Charles Schwab (00:08:46):

Polio. Polio was really a big problem back in that time, and a lot of kids, friends of mine, who got polio. And I remember kids being in lung machines and some who passed away, a disease that didn't have a solution. Among us children, money was, we didn't think about it. We didn't have it, so we made do. I raised chickens actually. The most fantastic animal in the world, so prolific. Chicken eggs, of course. The women in the area all wanted the manure for their gardens. My dad had some clients that were very successful, that were big time farmers, owned a lot of property. Remember one in particular had a house down at Pebble Beach, and so we went down to visit him. My father did point out their success to me. He said, "Well, they own 5,000 acres, or 2000 acres." I thought this was pretty impressive. He had a house in Woodland, California and a house down at Pebble Beach. I thought, "Wow, that's pretty cool. I think I'd like to do that."

(00:10:23):

I wasn't a great student in many respects. I spent a lot of time after school. My fear was my father thought I was stupid. And in many ways I felt stupid, by not being able to be as articulate as he was. He was very articulate. Slap me on the back and say, "Boy, you're really doing well, kid." I don't remember those moments at all. Became very apparent to me, I had a learning issue, but they didn't have the word called dyslexia then. Love comic books, oh my goodness. I got a lot out of the pictures that I wouldn't get necessarily in a block of words. That's why I really gravitated toward contemporary art and collected today. In school, I just worked harder, hacked my way through. It was ugly. It was not fun being zero. I wanted to get as far away from zero as I could.

(00:11:50):

My father said he bought some shares or something. There were the stock tables in the newspaper. I wanted to understand why these things went up and down in value and try to figure out what that was all about. Surprised we had that conversation, me and my dad. It became pretty obvious to me you buy them low and sell them high. It was a great moment in time. You wanted to please your parents, right? Being a very entrepreneurial or financially oriented kid, I knew that you needed to make money to spend money. Rather than watching the football game, I was underneath the stadium picking up coke bottles that people had dropped through the bleachers, turned them in for 5 cents a bottle. I wanted to get as far away from zero as I could. I was a tractor driver working in the agricultural fields, pack around big bales of hay and sack them up. Another summer job that I thought I could learn about insurance. I never sold a policy. I had a job selling installation, was made up of newspaper. Go door to door, demonstrate to them how great this installation was. It was a real joke. I never sold a single installation. I was too honest I guess. It was something else.

(00:13:26):

One memory, I was a switchman on a railroad. That was the year of, I think it was '57. It was a big recession in America and here's this music teacher, didn't have enough work to support his family, so he also was a switchmen, making the same amount of money I was per day, $19 a day. He said, "Don't end up like me." I felt really sad and impressed that he would leave that profession of music and do this. Wow. Made a big impression on me. Highly educated guy working as a switchman. It wasn't right.

(00:14:27):

We moved to Santa Barbara. Terrible in English, I was terrible in language. I took French. All I could do is get a D out of that thing at best. My dad was really upset with me. It was not a happy time for me. So I devoted my energies to golf. I was ambitious about my golf, loved that. It was really a fantastic boost in confidence. Our golf team in Santa Barbara High School played the freshmen at Stanford, so I got to see the campus and the coach. I was a very good golfer at the time. We almost beat the freshmen team as high school kids. The coach encouraged me to apply to the school. I think he wrote a good note to the admissions people; "Why don't we give him a chance?"

(00:15:59):

There I was. I'd never had such freedom in my life. Tuition then was $250 a quarter. No parents around, no demanding father, disciplinarian of all time. He wasn't there. I think he wished I'd been a lawyer, but I was not cut out to be a lawyer. I could memorize about three words, that was about it. That was not my cup of tea. All my friends were really smart. I almost flunked out of school that first quarter. Yeah. So that was embarrassing, so I knuckled down. Then found out I had to work harder at school than I ever thought to stay in, so I gave up golf then. That's all I did was study. I had a little time for anything else. Was able to get into business school. I was married with a new child. We lived in a little apartment above a garage. Pressure was on, baby.

Carrie Schwab-Pomerantz (00:17:24):

I am Carrie Schwab-Pomerantz. Born in Palo Alto, California, on the Stanford University campus. He's my dad. He was getting his MBA and my mom was an undergraduate. They laugh about me being born during finals. My dad did not become the Charles Schwab that people know until I was 25 ish, 24. As a kid, you don't really look at your dad that way. He's just your dad. We had just a real simple life and I don't know that I even understood what he did. I just know he went to the office every day. He worked long hours and he never had a lot of money. He was busy. I wouldn't say he was physically there for us, but I knew he loved us.

Charles Schwab (00:18:30):

There was some lapse in my part to being a great father. I was working probably harder than I should have. Their baseball game was going on and I was down working on the next office or something. I've been trying to make up for it ever since.

(00:18:54):

I was trying to figure out what I was going to do next. I loved to see companies grow and understand what that was all about, what creates good ones and the fundamentals of economic freedom. I went down to San Francisco to interview in the brokerage world, very formative years for me. I wasn't a salesman, I was an analyst and a portfolio manager. So, I had a lot of contact with a lot of brokers. They'd say, "Take us out to lunch, take us to dinner. Take us wherever the hell we want to go. Entertain us." Once they got their confidence, they could sell you anything basically and then you'd never see them again. They'd move on to a different firm. Some people would call it being a conman. So I began really understanding the brokerage industry as such, what I didn't want to be.

(00:19:57):

Say, "I've got a really good idea for you. It's going to go to the moon. You better hop on." That's the nature of Wall Street, you follow streams all the time, being creative. Services around investing was very high cost, tough to access. Only the wealthiest people in the world can participate. That was the industry. Inside information was rampant then.

Speaker 13 (00:20:30):

Relax, will you? Believe me, you made the right move.

Speaker 14 (00:20:32):

You really think so?

Speaker 13 (00:20:33):

Sure. We got the inside track. Listen...

John (00:20:38):

Hello?

George (00:20:38):

Listen, John, we've got a really fantastic opportunity to recoup our losses here.

John (00:20:42):

They're not our losses, George.

George (00:20:44):

Hey JP, where's that old killer instinct?

John (00:20:47):

Call me later. I got some things to do right now.

George (00:20:48):

Potter, this is a hot stock option.

John (00:20:50):

Yeah, I know. Call me later.

George (00:20:52):

John.

John (00:20:52):

Bye.

Charles Schwab (00:20:55):

It wasn't right. There had to be a change. I knew there was a business that people who wanted to buy and sell stocks on their own without the interference or suggestions of brokers. I knew there was a niche there, which I went after. So I started a company called Investment Indicators. We had managed accounts. We published twice a month a newsletter about investing. Most of the stuff being published was very biased. It was a sales brochure. So we changed that. I decided to change the name of the company. I owned the whole company, so looking for a name; Schwab Investment Company wasn't good, because it conflicted with somebody else and so on and so forth. Finally, I said, "How about just my name? Charles Schwab Company." Introducing discount brokerage to the world. We've got to make the benefits of capitalism available to everybody who chooses to participate.

Carrie Schwab-Pomerantz (00:22:36):

A kid on the playground said, "Did you know your parents are divorcing?" And I said, "What is divorce?" I didn't even know what it was. Some of it was that my dad was very focused on building a business and I don't think that went over well with my mom with three little children. Dad moved to an apartment building, a high rise, and we would make paper airplanes and throw them off the balcony. And then, when it would have a downpour in San Francisco, when there's big puddles at a corner of a stop, he would drive fast around the corner, so the splash. And of course we thought it was hilarious that he did that, so he would find another corner and go fast around it.

Charles Schwab (00:23:34):

I remarried in 1972 to Helen, Helen O'Neill. Highly supportive and that was one of the best decisions I've ever made. We ended up having two wonderful children, and I'd had three older kids from my first marriage. And still just beginning, just beginning.

(00:24:08):

Trying new things was okay on the West Coast. Silicon Valley was just beginning. We'd already had a history of innovation, where New York was so fixed in what they did. We do it our way. We've been doing it for 200 years. We were facing these entrenched companies, these huge investment banking firms; Bank of America, CityCorp, JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch. I was this little guy on the West Coast and we had no success really. That time period, you look at the stock market was not going up. It was going down mostly.

Speaker 17 (00:24:57):

A sudden cutoff of oil from the Middle East turned the serious energy shortages into a major energy crisis.

Charles Schwab (00:25:04):

Nixon was thrown out of office.

Speaker 18 (00:25:06):

There's the President, waving goodbye.

Speaker 19 (00:25:09):

President Nixon's helicopter going over the White House South Lawn.

Charles Schwab (00:25:11):

It was just a very difficult period. 120 Montgomery Street, the first office of Charles Schwab Company. And access to capital for me was a fundamental problem, because I couldn't access Wall Street. I figured they didn't want to finance their competitor. That was tough. I took the salesman out of the middle of the whole formula. They're despising me for what we were doing here out on the West coast. Venture capitalists turned us down. All these pressures simultaneously, just have to take it. Got to be a cool cat.

(00:26:01):

What we did was try to boost services and lower costs. If you're an entrenched business, you have no motivation to drop your prices, and so I was a pariah for sure. We were beginning to open offices and we would try to rent something up on the 20th floor. Where on the main floor, it might've been another brokerage firm offices, and they had such clout with the landlord that they threatened a number of places that they would leave their big 20,000 square foot place down, while we were renting something per a thousand feet upstairs, way upstairs out of nowhere in the clouds. This is ridiculous. We can't even rent a space. We were growing so fast, trying to raise capital and it was my responsibility to go get it.

(00:26:50):

So I looked around the room and the only guy who had any capital available was through the equity in his house, so I mortgaged my house. We could lose it if the business didn't do well, was simple as that. That was a huge negotiation with my wife. "You're what? Mortgaging the house that we live in, our kids? Think about that, Chuck." I said, "It's important for the future." I went to relatives, went to friends. "I hope Chuck doesn't come and ask me for money, because it's just not what I want to do." They regretted it later on. Probably would've been one of the best investments they'd ever made.

(00:27:53):

The magic moment, May 1 of '75. Mayday. Congress passed laws to outlaw fixed commissions. Free and open competition. In essence, really democratize the business, bring it open to anybody. If you got a 100 bucks, you're in. Articles in the paper, Merrill Lynch raised their rates. I was very happy that day, because I would've thought that Merrill would've dropped their rates substantially and we would've had no business, but they raised their rates on individual investors, not lower them. We dropped our rates. It just created a huge opportunity for us to take our little business and grow it like crazy.

(00:28:54):

So off we were. It was the beginning of an industry. So that's me in 1976; happy, the big flyer glasses. Looked like an airline pilot. Because we had so many orders coming in, we created a conveyor belt, six people on each side of the trading desk, people on telephone taking orders. It was all carbon copy, so you put the person's name, their account number, 100 shares of this. We'd write that all up, thank Mr. Jones, hang the phone up, put it in the conveyor belt, shoots down the conveyor belt to the trader at the end. He calls the order in and then the floor broker goes and executes it on the New York Exchange. A report comes back maybe a minute later that it's been executed and we'd have another person calling back with the report that you bought 100 shares. Might all be done in let's say 10 minutes. It was a whole lot of fun.

(00:30:02):

But nobody had heard of us. Everything changed with Dan Dorfman. Dan Dorfman was a very significant financial writer and he had the credibility and everyone read his column. He arranged lunch and we went to this wonderful place, the power room at the Four Seasons in New York. All these special tables, all these power people around the room, chairman of this bank and chairman of that bank. All these guys networking. And I started talking about this business, discount brokerage. He said, "Wow, are you kidding me? I can buy stock through you at this price?" I said, "Yeah." So he calls the waiter over, and he gave me a telephone. There was no cell phones then. It had a plugin someplace for the telephone. So right there at the table he called Merrill Lynch and said, "How much will it cost me?" And they quoted the thing. Then he called one of our offices, said, "How much will..." And we were, like I said, half.

(00:31:19):

And the next day he had this nationally syndicated thing about this new business. The whole world began to really know about what we were doing and so it just kept growing and growing. The volumes kept mounting. It was crazy.

Speaker 20 (00:31:42):

[inaudible 00:32:00].

Bill Gillis (00:32:04):

My name's Bill Gillis, proper name is William, born in Henderson, Kentucky in 1948 at 620 Clay Street, a four bedroom home that housed all 11 of us. Born to a Baptist minister and his wife. Fourth grade, my best friend, who's also name was Bill, we were inseparable. I went one day to his house to have dinner and we were at the table and his grandfather was there and he saw me and he stood up and said," I will not eat at a table with an N word." And I got up and stormed away. I left and was never invited back. So my father wanted to get out of the south, so his kids could have a better education. My older siblings still had to attend all black schools, so he integrated the schools in Evansville, Indiana, with me and three siblings, yes, and his pistol.

(00:33:21):

When we were going into the schools, my father told me that it doesn't matter that you stand out, because you're going to stand out. What matters to us is that you be outstanding. I went to Purdue, graduated double E, electrical engineering, and got hired by RCA as a circuit designer. I introduced the VHS brand VCR. Took 94%, 95% of the worldwide marketplace. As a result of that, I can say pretty honestly that I have a product in every American home. I, in his grandfather's eyes, was not good enough to be in his company. While I might not be welcome in their house, one of my products or services will be there. He who laughs last, laughs best.

Charles Schwab (00:34:37):

Fortunately, because I had many friends in the technology business here in the San Francisco Bay Area, and we were very early adopters on technology, way before Wall Street ever even thought about some of the stuff, we were there. We were able to buy the back office computer system, used a computer that we got from IBM, one of the most advanced ones at the time. This was 1979, hard to believe. We were always fussing with innovation around technology.

Bill Gillis (00:35:19):

I got a call Sunday morning, and that person was Chuck Schwab. They were looking for somebody to head their technology division, because they wanted to create online trading. There was no electronic trading at that point. Several people were trying to introduce electronic trading. None had done it.

Speaker 22 (00:35:41):

With us now in the studio is William Gillis. Bill is executive vice president of Schwab Technology Services, a division of Charles Schwab and Company.

Speaker 23 (00:35:49):

Welcome to the Schwab quote service. Please enter your account number

Bill Gillis (00:35:55):

And my password.

Speaker 23 (00:35:55):

So you're basically using just a telephone as a computer terminal to access another computer's database?

Bill Gillis (00:36:01):

That's exactly right.

(00:36:02):

Virtually everybody else was working on one thing; how do you get to the point that you can let investors trade electronically? And I said, "Well, people don't simply buy and sell only, first they need to do some research. They need to get news, quotes. Then they need to track their portfolio." I thought, "We've got a lot of work to do."

(00:36:27):

I'll just call up a portfolio and the order has been placed in our host computer system.

Speaker 23 (00:36:32):

And what you're doing here is not really sending an order to a broker somewhere. You're actually placing and executing the order yourself.

Bill Gillis (00:36:39):

That's correct.

(00:36:39):

The first and most comprehensive electronic brokerage services.

Charles Schwab (00:36:57):

Sort of like Facebook at the time, for us.

Chris Dodds (00:37:14):

So many of the great entrepreneurs had a reasonably fatal flaw in that they believed they could do every job in the company better than the person they had in that job in the company. He knows what he's good at, but he also knows there's lots of things he's not good at. Okay, if you're here, we got a huge dream. You're here. We need your help. We're a small company, but we have a big dream. It's democratize investing, to bring that to America, make people's lives better. We can help people achieve their dreams; retirement, send their kids to school, good schools. I felt that was such a noble endeavor and I still do.

Charles Schwab (00:38:08):

There I was, this little guy in San Francisco. I was building a new industry. I figured the old-fashioned exclusive one had to collapse.

Speaker 25 (00:38:23):

How do you remember all those names submitted by checks?

Charles Schwab (00:38:25):

Well, I get some help from a few people. I glad you pointed out-

Speaker 25 (00:38:33):

So what are these-

Charles Schwab (00:38:33):

The answer is yes.

Speaker 26 (00:38:36):

Down by a thousand.

Speaker 27 (00:38:39):

Hi.

Speaker 26 (00:38:41):

Add three quarters.

Charles Schwab (00:38:42):

They all made salaries. That was really revolutionary. We want to get everybody in. Here, in our business, we don't care how much you have. We just want to make sure you become an investor. Here's this little guy from the West Coast, undermining Wall Street.

Speaker 26 (00:39:23):

I had all this stuff in the [inaudible 00:39:24] and all that kind of stuff. I didn't know where to... Okay, good.

Speaker 27 (00:39:36):

That's where to go.

Speaker 26 (00:39:37):

You got it. I'll give him a call.

Charles Schwab (00:39:42):

But then I had another problem. I had a problem of growth; how to manage and how to finance growth. New offices, new equipment, new software, hiring new people, training new people, all those things take capital.

Chris Dodds (00:40:06):

B of A, Bank of America, was a colossus. It was in that big brown building towered over the city.

Charles Schwab (00:40:14):

There was no bank that had a better reputation than Bank of America. It could do no wrong.

Chris Dodds (00:40:18):

It was the pillar of the establishment, the number one bank in the country.

Charles Schwab (00:40:23):

If you were living in California, there was a Bank of America almost on every corner in your community. My good friend, Steve [inaudible 00:40:32], he was the head of strategy for the Bank of America at the time. We were the new kid in town and they thought we could help them in their freshness of what they needed to offer to their public. Huge potential for them. He liked the company so much that instead of lending money to us, they wanted to buy the whole company. "What's the number?" Oh my God, that got my attention. $40 million. $40 million, I don't think I had $4,000 to my name at the time. So, they ended up proposing a deal to me. It meant that this little baby I had, the Charles Schwab and Company would have plenty of resources available to it. For me, I didn't know what to do. I wanted to turn the company around. I wanted to make things better and I had my responsibility to my employees. That was my baby. I didn't have to make that struggle anymore. I could just grow the company. So we became a subsidiary of the Bank of America. Now I don't have to worry about money anymore.

(00:41:51):

If the B of A endorsed it, it's got to be something really important. Our reputation just zoomed. Next three or four years, we grew amazingly. In addition, I was invited on the B of A board of directors. I represented 1% of the outstanding stock, the largest shareholder in Bank of America. I was the youngest person on that board by many years. Wally Haas, head of Levi Strauss, Andy Brimmer, first African-American on the Federal Reserve Board, Robert McNamara, who had been Secretary of Defense. I was quiet as a mouse there the first couple years on that board. Here I was on the board of directors of this bank now who controlled us, controlled a lot of our destiny at Schwab and the employees I had. I had to make sure our parent was going to be successful too. I was convinced by my ad guys that a real person should be behind the company. Eventually, TV commercials.

(00:42:49):

Big discounts, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. I'm Charles Schwab, and that's the way I see it, from the investor's point of view.

(00:42:56):

Our number one commitment is to serve our customer with integrity and, for sure, safety of their assets.

(00:43:04):

That was not easy for me to do that, the guy who can't remember three words in a row, but it worked, it worked big time.

Speaker 28 (00:43:12):

I read it every day for news around the USA.

Charles Schwab (00:43:17):

I read it every day for business that really pays.

Speaker 29 (00:43:22):

At home or away, I read it everyday. USA TODAY.

Speaker 28 (00:43:27):

USA TODAY.

Charles Schwab (00:43:28):

I was so bad at singing. It was pretty funny.

Chris Dodds (00:43:39):

I joined Schwab as employee number 981 on October 26th 1986. I was a 26-year-old guy. I was the numbers guy, low man on the totem pole. I'm sure B of A had a planning analysis staff of, who knows, hundreds of people. At Schwab, planning analysis was two people; Ray Carvey, planning, and then they hired in young Chris Dodds. I was analysis. We had two people. 101 Montgomery, were the headquarters where I first started working. And we're waiting for the elevator and lo and behold, who comes up to get on the elevator with us is Mr. Schwab. Wow, this is really, really cool. I remember thinking, "I thought he'd be a lot taller." And he says, "Hi Ray, how you doing?" And Ray says, "Chuck, I'd like you to meet somebody. This is the new guy that joined us in planning analysis function." And he says, "Hey, how you doing?" And I said, "Oh, Mr. Schwab, how are you? So nice to meet you." And in his usual way, he gives you that, "Just call me Chuck."

Speaker 30 (00:44:40):

Ladies and gentlemen, Governor Ronald Reagan.

Ronald Reagan (00:44:45):

Where once there was a great confident roar of American progress and growth and optimism, there is now the eerie ghostly silence of economic stagnation, unemployment, inflation, and despair. The average American is 8.5% poorer than he was four years ago.

Charles Schwab (00:45:06):

I decided the day before the election, I'm going to keep the company open up all night long to let people put orders in as they saw the election come in. People loved it. Eventually 24/7. Guess what? The rest of the industry began following us. '80s were great. Free and open competition. I don't think I've ever had a trader come to me and say, "Oh boy. I just traded my brains out and paid so much in taxes. I've had a great time. Thank you Mr. Schwab." That never happened.

Speaker 31 (00:45:47):

Investors look at the economy as a glass that is half full.

Charles Schwab (00:46:02):

It became obvious to me that there was a huge underlying problem of the inefficiencies of the bank itself. We had something like 70,000 employees. We should have had something like 50,000. No competition from the outside, also bad foreign loans. We just needed to fess up to the issues that we were dealing with, as things were getting more and more competitive. I talked to the CEO about things that we should do, and he said, "I can't do that." I didn't have the cooperation of management at the time, but I thought maybe I could convince some of the guys on the board. Maybe we should look at some of these things.

(00:46:58):

So I gathered a group of people at McNamara's home in Washington, D.C. Put forth, "Here's the problem and here's how I would fix this thing, or begin fixing this thing." Becoming more efficient, reducing some of their personnel, improving their profitability. And that went over like a lead balloon. Much to my disappointment, my parent company was getting in trouble. Their premiership seduced me into merging with them, but there I was, found myself in the middle of a real issue much bigger than I'd ever faced before.

(00:47:37):

In '85 and '86, the bank started selling many of their assets. I had all my assets tied up in the Bank of America and their stock price kept dropping. I was drowning. And I had my responsibility to my employees, that's why I resigned from the board. They wanted me to stay on the board. They didn't want this controversy at all. So, I resigned. Thank you very much. See you later. And then of course, when I did resign, they immediately fired me from the Schwab board. Yeah. Charles Schwab and Company. That was my baby, a compelling reason why I should try to get myself out of the bank and make a plan to try to buy the company back. Certainly I wanted to go the peaceful route, but they were jacking me around so much that I had to make sure that they knew I was going to file the damn lawsuit.

Chris Dodds (00:48:45):

When B of A bought Schwab for 57 million, I think it was, they paid for it by giving B of A stock, so they didn't get cash, they got B of A stock. Trying to rescind the original transaction was certainly considered. You would've had to prove that B of A knew about its problems and did not tell us about them adequately. I think that would've been a very hard road to hoe and prove, and it would've taken a lot of time and time in the public sphere perhaps, what does that translate to? That translates into a lot of Schwab clients saying, "Hey, what's going on? Are things really okay with this brokerage firm? Should I really be here? Are you guys going to be around? Is there a problem?" We didn't want to take that risk. You could be impacting the value of your asset, i.e. Schwab.

(00:49:37):

Word filtered down that Chuck wanted to buy the company back from B of A. My boss and various others were saying, "Well, who can help us do this?" I volunteer. And I was a young man, I was 26 years old. I hadn't been in negotiations before. So we start talking about how we're going to go about valuing Schwab. It had never really been done before. How are you going to value this company? Putting a price tag on it to go back and propose; this is what we'll pay B of A to buy back the company

(00:50:15):

In a more industrial context, the value of the firm's assets is held in things that are physical, that are tangible, that have much more readily ascertainable values. Whereas with our firm, we had some computers, desks and chairs and branches, but really all the value of the company was based on services that you provided to customers. We had to come up with a price that B of A would say, "That's a reasonable price." Not, "Are you crazy? Get out of here. I'm not ever going to speak to you again. We're selling it to somebody else, Chuck. Thanks very much."

(00:50:52):

I had no other assignment. That was all I did. Four or five months worth of very late nights, very long negotiations. Finally, we came across the most important point in our case. B of A did not own the name Charles Schwab. They did not own Chuck's likeness. He was the public face of the company And they did not own him. The brand was inextricably tied up with this person, with the glasses on and he's in all the ads and he's an affable looking gentlemen, leaning against the computers or leaning against a desk where there's a ticker tape in the background. Okay, you can do that. You can sell Charles Schwab and Co, Inc, to somebody else over there. Fine. You don't get Chuck's name and you don't get Chuck's likeness, and all the ads which everybody knows is the face of this company. How are you going to sell that? And that was a very real consideration and a very real weapon. But eventually it all came together. March 31st 1987 was a day that I know I will never forget,

Charles Schwab (00:52:04):

So, they made a lot of money off of us. A lot of people don't realize that. They thought I was some crazy entrepreneur that left and bought it back for pennies on a dollar. It's not true. I paid them dollars on the pennies. As it turned out, people recognized Schwab as being me and the name, obviously my name.

(00:52:29):

I'm Charles Schwab, and that's a promise.

(00:52:31):

And so they had a weak position.

Chris Dodds (00:52:37):

We had an all company, all hands meeting up in the ballroom of the St. Francis Hotel. The whole company was there. To this day, I've never ever seen Chuck that happy.

Charles Schwab (00:52:50):

Oh, yeah?

Chris Dodds (00:52:52):

"Ladies and gentlemen, Chairman, CEO of the Charles Schwab Corporation, Chuck Schwab." I swear to God, I thought he floated across the stage. He was so [inaudible 00:53:01], so happy. Independent Schwab in charge, completely in charge of our own destiny. I will also never forget going home to my wife that night and saying, "MJ, I am never going to work anywhere else again. I'm never going to work anywhere else again." And I never did.

Charles Schwab (00:53:37):

The freedom came in March 31 of '87. As soon as we did the transaction, I thought we'd better go public in order to pay down some of this debt, because I was very uncomfortable with long-term debt, no matter what style it was in. If you've ever borrowed money, you borrow money and you have to pay it back, and that's a big mountain to climb. So, how do you do that? In my case, it was to go public and the quicker I did that, the happier I was going to be.

Chris Dodds (00:54:15):

By the time the IPO went off, we were all really tired. This had been a serious, serious 11 months.

Charles Schwab (00:54:22):

We we are all in a moment of euphoria.

Chris Dodds (00:54:25):

Finally, we're good. So that was just a big relief.

Speaker 32 (00:54:28):

[inaudible 00:54:37].

Speaker 33 (00:54:28):

[inaudible 00:54:39].

Speaker 34 (00:54:42):

Today is Black Monday, the day the Dow dropped more than 500 points, the day the Dow dropped more than 22%, almost double the rate of the Black Monday that signaled the beginning of the crash of 1929. It's around the world, stock markets fell faster than a skydiver without a parachute, the panic starting in Tokyo this morning while the west slept. Then, like a plague, sell fever headed west. The London Financial Times Index down more than 183, the biggest one day drop in Britain's history.

Speaker 35 (00:55:15):

This panic. Everyone's in panic.

Speaker 36 (00:55:16):

Everybody, we're trying to find a bottom. This has to be the bottom. And then they trade five points lower than that.

Speaker 37 (00:55:21):

Investors have looked at the economy as a glass that is half full. Now they're seeing it as half empty.

Speaker 38 (00:55:28):

The results of the decline will hit millions of people in their investments, pension plans, their mutual funds, and eventually every segment of the economy. But it only got worse.

Chris Dodds (00:55:39):

I don't know that any of us did anything that day, other than literally watch the stock price. I tried to not be awestruck. Can all stocks actually go to zero?

Charles Schwab (00:56:13):

People, they buy in for the promise that your company's going to grow. And so everyone was now losers in the company we took public. That was not a good feeling, not fun. As we fell into the elevator shaft of the crash of '87 and we were right in the middle of it, it wasn't a brand new concept to me for sure. I had lived through these down markets before. I just didn't realize it would come this quickly after going public. It doesn't go on forever. You can name many, many cycles like that over the years. Stroke of luck that I had raised this equity capital, reduced my debt and we had to rebuild the whole thing again. Took about a good year before it turned around, but that's the nature of the beast we have. Up and down, depression to exuberance, depression to exuberance. You just have to be able to understand that and deal with it emotionally. Something will happen to make things better.

(00:58:01):

It always happens. It always comes through. It never seems to come through as quickly as you want, but a little bit of patience does work wonders.

Speaker 39 (00:58:14):

Welcome.

Speaker 40 (00:58:18):

That little mark with the A; @nbc.ge.com. I mean what is internet anyway?

Speaker 41 (00:58:22):

It's a giant computer network made up of universities and everything all joined together.

Speaker 42 (00:58:26):

Right.

Speaker 40 (00:58:27):

And others can access it?

Speaker 42 (00:58:28):

Right.

Speaker 41 (00:58:28):

And it's getting bigger and bigger all the time.

Charles Schwab (00:58:30):

The introduction of online trading, we were very early on that way before internet. We used CompuServe and we used AOL.

Speaker 43 (00:58:39):

In 1981, only 213 computers were hooked to the internet. As the new year begins, an estimated 2.5 million computers will be on the network.

Charles Schwab (00:58:48):

In '95, '96, internet came and we were on top of that as hard as we could be, and usually we were ahead of the customer. We knew what they wanted.

Speaker 44 (00:58:57):

You can read business the week online before it hits the newsstand. Update your stock portfolio every 15 minutes.

Charles Schwab (00:59:02):

I certainly knew in my mind that we had a great business opportunity ahead of us; better service, lower prices, faster transactions. We want to get everybody in. Up and down. Depression to exuberance, depression to exuberance.

Speaker 45 (00:59:24):

Prices continue to fall. Across the country, the median home price is now down 2.7% from a year ago.

Speaker 46 (00:59:30):

If you're trying to sell it, you know it is not easy. The housing market is in a slump.

Speaker 47 (00:59:35):

Home foreclosures are up in this country and it is not getting better.

Speaker 48 (00:59:48):

It was a manic Monday in the financial markets. The Dow tumbled more than 500 points. Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy. 25,000 employees will be liquidated.

Speaker 49 (01:00:00):

How are you feeling?

Speaker 50 (01:00:01):

How do you think?

Speaker 48 (01:00:02):

Merrill Lynch, fearing it could be next, agreed in an act of desperation to a shotgun marriage with Bank of America.

Charles Schwab (01:00:10):

Crazy

Speaker 51 (01:00:11):

Breaking news that is shaking the very foundations of Wall Street.

Speaker 52 (01:00:15):

The Dow plunged nearly 700 points down.

Speaker 53 (01:00:17):

Some people say this doesn't stop until the housing hits bottom. Do you think that's true?

Speaker 54 (01:00:21):

I think that's probably correct.

Speaker 55 (01:00:23):

And the Dow took a breathtaking nose dog.

Speaker 56 (01:00:25):

Massive layoffs.

Speaker 57 (01:00:26):

Biggest loss in the history of Wall Street.

Speaker 58 (01:00:28):

US economy is under siege from all sectors.

Speaker 59 (01:00:31):

15 million Americans out of work.

Speaker 60 (01:00:33):

Shock waves from the US Financial crisis are reverberating around the world.

Speaker 61 (01:00:37):

European markets worst one day losses since 9/11.

Speaker 54 (01:00:40):

The fifth time we've seen this movie, and you sit on the edge of your seat and you yell at whichever character it is; "Don't go into that woodshed," but they keep going in.

George Bush (01:00:49):

This is an extraordinary period for America's economy. We are in the midst of a serious financial crisis. We've seen triple digit swings in the stock market. Major financial institutions have petered on the edge of collapse and some have failed.

(01:01:04):

Many Americans have felt anxiety about their finances and their future. So I propose that the federal government reduced the risk posed by these troubled assets and supply urgently needed money so banks and other financial institutions can avoid collapse and resume lending.

(01:01:20):

Wall Street got drunk and we got the hangover.

Speaker 63 (01:01:22):

You went with the TARP program. A lot of people now call it the bank bailout, and they hate it.

George Bush (01:01:28):

Yeah, they do hate it. I can understand that. Do you adhere to your philosophy and say, "Let them all fail"?

Speaker 63 (01:01:34):

Free market.

George Bush (01:01:35):

Yeah, free market. Or, do you take taxpayer's money and inject it into the system in hopes that you prevent a depression? And I chose the latter.

Speaker 64 (01:01:46):

Did you take TARP?

Charles Schwab (01:02:13):

No. I was responsible for my own.

(01:02:13):

Look at what we have made. I'm so lucky to have been in San Francisco, a place with these incredible ideas. It was a time to give back to the city.

Neal Benezra (01:02:40):

A good painter can be a very good technician, create a well painted picture just in terms of the quality of the brushwork and the use of color and so forth and so on. A great artist distinguishes him or herself by showing you something in their work that you'd never seen before and probably couldn't have imagined, that it opens up a whole nother world. You'd be interested to know that some of the best contemporary artists are also dyslexic and that their creativity is expressed not in words and writing, it's in images and visual images, an important thing for Chuck.

Speaker 66 (01:03:28):

Great.

Charles Schwab (01:03:29):

How are you?

Speaker 67 (01:03:29):

Sir, it's a pleasure to see you.

Charles Schwab (01:03:30):

Good to see you, Sir.

Speaker 67 (01:03:30):

Good to see you.

Charles Schwab (01:03:34):

Uh oh, you got yourself on film.

Speaker 67 (01:03:36):

[inaudible 01:03:36]. Shoot the video there, Greg.

Charles Schwab (01:03:47):

You're all right? How are you? We like contemporary art, a lot.

Neal Benezra (01:04:04):

This became a new endeavor for him, to lead the board of a major American museum dedicated to contemporary art. At a certain point in his life, it made sense for him to spend a tremendous amount of time on this and really give himself over to this. We imagined an expansion of the museum. This was a dream that Chuck and I had. Well, okay, so now it's 2010 and we're in the middle of a financial crisis.

Speaker 68 (01:04:38):

Wall Street nearly flatlined, after President Obama signed the stimulus into law.

Speaker 69 (01:04:42):

... request for another $21 billion in emergency health.

Neal Benezra (01:04:45):

There was a lot of skepticism that we would be able to raise the money we needed to raise. This is the largest capital campaign in the history of San Francisco. The symphony and the ballet and the opera and the fine arts museums, they've all had big capital campaigns. Nothing like this. Is this realistic? In the face of a recession, maybe we're crazy to even try this right now. Maybe we should just wait a while. And Chuck, ever the optimist, said, "No, let's go for it." The first thing that happened is we had to hire an architect. $660 million.

Charles Schwab (01:05:28):

When Neil had a model made of the new museum, and so we had it all boxed up in nice suitcase.

Neal Benezra (01:05:36):

And I remember we got in the car and we looked at each other and said, "We can do this."

Charles Schwab (01:05:43):

We had a regular pitch that we put together, begging for money.

Neal Benezra (01:05:47):

He would always talk about how he wore out the knees in his pants asking people to help with this. But Chuck had this nice way with people, that modesty enabled people to feel as though they were really part of something. They weren't peripheral, they were central. And; "We need your help and you can be an important part of this."

Charles Schwab (01:06:11):

You believe in what you were doing so, so much that you'd do anything to help finance the operation.

Neal Benezra (01:06:26):

With this deal getting done, it raised the bar for everybody else on the board and the community of the museum. They were doing something special down there at SFMOMA. So it inspired the city.

Latasha Poindexter (01:06:48):

The first time I went, oh, did you ask that question? I was there to attend the grand opening. I made it a grand entrance. I put on my best attire and I rented a limousine. Let's give them something to talk about. When I stepped out of the limo, they thought it was somebody else. They couldn't believe; "That's the security guard?" That's what they said. "Whoa." So, of course I'm going to go and support. I wouldn't have missed it. And I decided to one up them. I stepped out a limousine. I felt like representing, just pull out all the stops. You know what I'm saying?

Neal Benezra (01:07:28):

After the last big ribbon cutting event, I need to be hospitalized. I'm so exhausted, really tired. And so I had my weekly meeting with Chuck and I limped in. First thing he says, "All right," he says, "What's next? Now what are we going to do?"

(01:07:46):

So the story of this, it was painted in 1940 for an international exposition on Treasure Island. Nazis are marching through Europe and Churchill is pleading with Roosevelt to get into the war. So this side is American industrialism and there's Henry Ford and so forth. On the left-hand side, there are four more panels still coming. It's all about Mexico.

Charles Schwab (01:08:20):

Oh my goodness.

Neal Benezra (01:08:22):

And this has been sitting at City College since 1960.

Charles Schwab (01:08:26):

How's it been preserved? Great colors still, really vivid colors.

Neal Benezra (01:08:30):

Yeah. Well, the colors in fresco don't fade.

Speaker 70 (01:08:33):

So, fresco is fresh in Italian and it means that the plaster hasn't fully set or cured yet. And so the pigments are...

Neal Benezra (01:08:39):

So the paint is in the plaster.

Charles Schwab (01:08:43):

It's [inaudible 01:08:43].

Neal Benezra (01:08:43):

I think of this as the greatest work of art in San Francisco that pretty much nobody's ever seen.

Charles Schwab (01:08:47):

Yeah.

(01:08:48):

I got a lot of pictures that I wouldn't get necessarily in a block of words. It was a huge connection I think between contemporary art and what I've done professionally. And I think seeing artists do what they do, given me somewhat of permission to do it in our business. Think of it a different way than what was ever done before.

Carrie Schwab-Pomerantz (01:09:41):

My dad once told me it was the greatest gift he'd ever given me. He's probably not going to remember this. It was probably about five to seven years ago. We were talking about family and so forth and he said, "Carrie, you remind me of me." He said, "Don't change." Some people, you could say, "Ah, thanks a lot. I don't want to be like you." But my dad broke down a lot of barriers for our industry. He cares about the community in a big way. I would be proud to be like him. Now I'm getting teary-eyed.

Charles Schwab (01:10:25):

When do I get tears? Bringing these kids along and seeing them as babies and now it's full adults. That's great. I actually have 13 grandchildren, five wonderful children, and wonderful, smart, attentive, great parents. It does make me extraordinarily proud and still just beginning. Just beginning. I get tears when we raise a flag. These are proud moments. It's meaningful to me. It's not as meaningful to maybe younger generations, but my generation, having come through so many wars and so many things, how we persisted. Up and down, depression to exuberance. We go through struggles and then great successes to depression, to exuberance. Depression. Persistence, it's the heartbeat of this country.

Latasha Poindexter (01:13:05):

We are going to have to redefine what it means to be American. Yeah. We don't have the definition. We've got to get back to work being in vogue. Yeah, in vogue. To contributing. Being a part of something big, or bigger than you, because that's what America's all about. We're all about making, building, creating, competing. That's right. That's what gets me up in the morning. It's not coffee. No. Me? I would like to leave more than my dad left.

Speaker 7 (01:13:59):

All right. If you're ready, Andre from Aunt Tash.

Latasha Poindexter (01:14:00):

Oh, ain't that pretty.

Speaker 7 (01:14:00):

From Auntie Tash.

Latasha Poindexter (01:14:07):

My nieces and nephews, they don't have to start from zero, like I started from zero.

Speaker 7 (01:14:21):

... from Aunt Tash.

Latasha Poindexter (01:14:21):

Now, come give me your auntie a hug, boys.

(01:14:23):

My dad, he had a little small retirement with the trucking company he worked for and now his father left him a shoebox. And what was in the shoebox was a pair of old tap shoes. That's why I'm here, so I can leave a little something more than a pair of old tap shoes.

(01:14:58):

I just sent my brother a snapshot of what's in my account, just recently. Yeah. Of course, that's got his competitive juices going, but he's going to have a hard time trying to catch me. Thanks to Chuck.

(01:15:34):

Yeah. Good luck, brother. Yeah. This is one race I'm going to beat him in.

Charles Schwab (01:16:51):

I am Charles Schwab and that's the way I see it; from the investor's point of view.